Chapter 2

The Making of

Jammu & Kashmir StateAcquisition

of Kashmir valley by Gulab Singh in 1846 and its incorporation in his vast

Dogra Kingdom marked the beginning of a new and, from the point of view

of the present study, a crucial phase in the long and chequered history

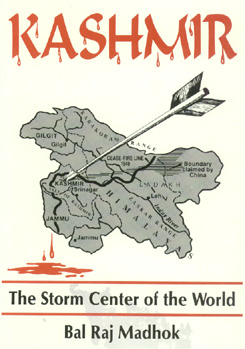

of the land of Kashyap. The developments which have put Kashmir on the

map of the world as a storm centre are directly linked with the international

developments connected with the steady expansion of the British, the Russian

and the Chinese empires in the 19th century. With the annexation of Lahore

kingdom by the British which made the British Indian empire contiguous

to Afghanistan and push of Czarist Russia toward Hindu-Kush mountain. Jammu

and Kashmir state became the meeting ground of the three empires the British,

the Russian and the Chinese. The global interests of the British then demanded

that they should have a direct grip over J & K state. This impelled

them to put pressure on its Dogra rulers to make them amenable to their

game plan.

It is, therefore,

important to have a close look on the kingdom that Gulab Singh built, its

geographical position, demographic complexion and the place of vale of

Kashmir in it.

An objective

assesment of Gulab Singh who carved out for himself and his successors

a virtually independent kingdom of over 84,000 sq. miles stretching from

the pIains of Punjab to the Pamirs, Sinkiang and Tibet at a time when other

Indian kingdoms, some of which had a hoary past, were falling flat like

houses of cards before the fast moving British stream roller, is also relevant.

Born in 1792,

Gulab Singh was a scion of the ruling family of Jammu which was one of

the 22 petty Rajput states in which the sub-mountainous "Kandi" area to

the north of the Punjab was then divided. He left his home at the age of

seventeen in search of a soldierly fortune. He intended to go to Kabul

and join the army of Shah Shuja, but his companions refused to go beyond

the Indus. Then, he decided to join the service of Maharaja Ranjit Singh

who was at that time making his mark in the Punjab. He joined the army

of Ranjit Singh in 1809, the year in which the latter signed the famous

treaty of Amritsar with the British which gave him a free hand to expand

his kingdom to the West of the Sutlej.

Gulab Singh

soon distinguished himself as an intrepid soldier with a high sense of

duty and devotion to Ranjit Singh. He made his mark in many a campaign

which Ranjit Singh undertook to conquer Kangra, Multan and Hazara. He also

introduced his two younger brothers, Dhian Singh and Suchet Singh, in the

court of Ranjit Singh. Both of them later played a very important role

in the making and moulding of the kingdom of Lahore.

Ranjit Singh

rewarded Gulab Singh by appointing him Raja of his ancestral principality

of Jammu and put the "Tilak" on his forehead with his own hand in 1822.

Thus, after thirteen years of absence from Jammu, he returned to it as

its ruler under Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Having thus secured a foothold in

his ancestral home, he assiduously tried to extend his influence in the

surrounding areas while serving Ranjit Singh whenever and wherever required.

His interests at the court of the Lahore kingdom where well looked after

by his younger brother, Raja Dhian Singh, who rose to be its Prime Minister.

As Raja of

Jammu, Gulab Singh raised an army of his own which included such notable

soldiers as Wazir Zorawar Singh. He conquered the Principalities of Bhimber,

Rajouri, Bhadarwah and Kishtwar which extended the limits of his state

to Rawalpindi in the west and border of Laddakh in the north-east. The

valley of Kashmir which had been annexed by Ranjit Singh earlier was, however,

ruled by a separate governor as a province of the Lahore kingdom and Gulab

Singh had nothing to do with it.

In 1834, Gulab

Singh Decided to extend his sway to Laddakh and Baltistan. He entrusted

this job to Wazir Zorawar Singh who successfully led six expeditions into

Laddakh between 1834 and 1841. Since Kashmir valley was not under Gulab

Singh at that time, the route followed by Zorawar Singh was through Kishtwar,

Padar and Zanskar. It was more difficult but much shorter than the route

passing thrcugh Kashmir valley via Yojila pass.

After having

conquered and added the kingdoms of Baltistan and Laddakh to the territories

of Gulab Singh, Zorawar Singh decided to go forward and conquer Tibet.

It was a most adventurous move. He left Leh with an army of about 5000

Dogras and Laddakhis in May 1841 with a pledge not to return to Leh till

he had conquered Lhasa. After overcoming the Tibetan resistance at Rudok

and Tashigong, he reached Minsar near lake Mansarover and the holy Kailash

mountains. From there he advanced to Taklakot which was just about 15 miles

from the borders of Nepal and Kumaon and built a fort there. Here he met

two emissaries, one from the Maharaja of Nepal and the other from the British

Governor of U.P., then called North-West Province. The British were not

happy over Zorawar Singh's advance because they dreaded a direct link up

of Lahore kingdom with the kingdom of Nepal. They had in fact been putting

pressure on Lahore Darbar to press Gulab Singh to recall Zorawar Singh

and vacate the Tibetan territory already occupied by him. Zorawar Singh

was, however, blissfully ignorant of these moves. But an intense cold weather

and the long distance from his base at Leh forced him to stop further advance

and encamp at Taklakot for the winter.

In the meantime,

the Lhasa authorities sent large reinforcements to meet him. On learning

the approach of this new army from Lhasa, Zorawar Singh, intrepid and dashing

as he was, decided to take the offensive against the advancing army instead

of waiting for it to attack him. It was not a very correct decision. His

supply position had become extremely bad and his Dogra soldiers had been

reduced to sore straits by the intense cold. Many of them were frost-bitten

and incapable of moving about. As a result the battle of Toyu, which was

fought on the 11th and 12th December, 1841 at a height of about sixteen

thousand feet above sea level proved disastrous for Zorawar Singh who died

fighting. Dogra army like Napolean's army in Russia, was destroyed more

by cold then by the Tibetans.

The death of

Zorawar Singh was a grave blow to Gulab Singh's prestige in Laddakh where

people rose in rebellion aided and abetted by the advancing Tibetan army.

A new army was then sent from Jammu under the command of Dewan Hari Chand

which suppressed the rebellion and threw back the Tibetan army after inflicting

a crushing defeat on it which convincingly avenged the defeat of Toyu.

Thereupon the Tibetan Government approached for peace. A peace treaty was

signed on the 2nd of Asuj, 1389 Vikrami (September, 1842) by Diwan Hari

Chand and Wazir Ratnu on behalf of Gulab Singh and Kalon Surkhan and Depon

Pishy on behalf of Dalai Lama. By this treaty, the traditional boundary

between Laddakh and Tibet 'as recognized by both sides since olden times,'

was accepted as boundary between Jammu and Tibet. The village and area

around Minsar near Mansarover lake which was held by the Rajas of Laddakh

since 1583 was, however, retained by the Jammu government. The revenue

from Minsar which lies hundreds of miles inside Tibet was being received

by the Jammu and Kashmir Government regularly till 1948. This treaty of

1842 settled the boundary between Laddakh and Tibet in unequivocal terms

leaving no cause for any kind of border dispute in this region.

While Zorawar

Singh was making history in Laddakh and Tibet, the kingdom that Maharaja

Ranjit Singh had built had fallen on evil days. Ranjit Singh died in 1839.

His death was signal for the worst kind of anarchy and mutual killings

in the history of the Punjab. The Sikh nobles who had been jealous of the

ascendancy of the Dogra brothers in the Lahore Kingdom, now began to conspire

against them with the help of Sher Singh who succeeded to the gaddi of

Ranjit Singh after the death of Kharag Singh and his son Naunihal Singh

in rapid succession. The situation was made much more difficult by the

presence of British troops in Peshawar in terms of the Tripartite Treaty

of 1838 by which Ranjit Singh had agreed to help the British to put Shah

Shuja on the throne of Afghanistan. Gulab Singh was then at Peshawar to

assist the British on behalf of the Lahore Durbar. The Muslim battalions

of the Punjab army had refused to fight against the Muslim Afghans and

had mutinied. The party in power at the Lahore court was, if not actually

hostile, at least indifferent to the fate of the British troops still stranded

in Afghanistan. Gulab Singh well understood the situation and proved very

helpful to the British in terms of the Tripartite Treaty in getting them

out of a difficult situation. The British felt gratified and at one stage

actually proposed that he might be given possession of Peshawar and the

valley of Jalalabad in return for Laddakh for the timely help rendered

by him. But he refused the offer both on moral as well as practical grounds.

Laddakh had been conquered by him through his own army and was contiguous

to Jammu while Peshawar and Jalalabad would be too far removed from his

ancestral base at Jammu. But the assistance he rendered created a high

respect in the minds of the British for him and his Dogra army.

Things moved

rapidly in Lahore after 1841. Both Dhian Singh, the ablest leader and Prime

Minister of the Lahore Kingdom, and Suchet Singh were brutally murdered.

Maharaja Sher Singh too was murdered and the infant Dalip Singh was put

on the throne with a council of regency dominated by his mother Ranichand Kaur. Gulab Singh escaped because he kept away from Lahore most of the

time. These murders of his brothers naturally left him cold toward the

affairs of the Punjab and he began to concentrate on building his own power

in Jammu. He took no part in the first Anglo-Sikh war which began in 1845.

The Lahore Darbar wanted him to come down to Lahore and lead its armies.

Had he agreed, it would have made a world of difference for both sides.

His advice to the Council of Regency at Lahore to avoid war with the British

was not heeded.

After the defeat

of the Sikh army at Subraon in February 1846, peace negotiations were opened.

Raja Gulab Singh was given full powers to negotiate on behalf of the Lahore

Darbar. The British Government were well aware of the resourcefulness of

Gulab Singh who was reported to have advised the Lahore Darbar to avoid

pitched battles with the British and instead cross the Sutlej and attack

Delhi with the help of some picked cavalry regiments. The British were,

therefore, very anxious to secure his friendship. He was offered a bait

that he would be recognized as an independent ruler of Jammu & Kashmir

if he withdrew his support from the Lahore Darbar and made a separate deal

with the British. Gulab Singh replied that he could not negotiate with

the British about his own possessions while he was acting as an envoy for

Dalip Singh, the king of Lahore. He continued the negotiations on behalf

of the Lahore Darbar which culminated in the Treaty of Lahore signed on

9 March, 1846.

According to

this Treaty of Lahore it was agreed to by the Lahore Darbar to cede the

territory between the Beas and the Sutlej to the British and Pay 15 lakh

pounds (Rs. One Crore Nanak Shahi) as war indemnity. Lal Singh, the then

Prime Minister of the Lahore kingdom, had no love lost for Gulab Singh.

He offered to the British the hill territories of the Lahore Kingdom including

Jammu & Kashmir in lieu of the indemnity. His idea was "to deprive

Gulab Singh of his territory and give the British the option either of

holding Kashmir which would have been impossible at that time because of

the long distance and intervening independent State of Punjab or to accept

a reduced indemnity."2 This offer, however, suited Gulab Singh. The original

offer of making him an independent ruler of Jammu & Kashmir was revised.

But now it was conditioned by his taking the responsibility of paying the

indemnity which had been made a charge on this territory by the cleverness

of Lal Singh.

Gulab Singh

agreed to pay the money to the British and they recognized him as an independent

sovereign.

Accordingly,

a stipulation was made in the Treaty of Lahore by which Maharaja Dalip

Singh of Lahore agreed to 'recognize the independent sovereignty of Raja

Gulab Singh in such territories and districts in the hills as may be made

over to the said Raja Gulab Singh by a separate agreement between him and

the British Government.'

Seven days

later, on the sixteenth of March, 1846, the Treaty of Amritsar was signed

between Maharaja Gulab Singh and the British according to which Gulab Singh

was recognized as an independent ruler of all the territories already in

his possession together with the valley of Kashmir which until then formed

a separate province of the Lahore Kingdom.

According to

the Treaty of Amritsar, the British transferred for safe independent possession

to Maharaja Gulab Singh and his heirs all the hilly and mountainous portions

with its dependencies situated to the east of the river Indus and West

of the river Ravi including Chamba and excluding Lahaul - being part of

the territories ceded to the British Government by the Lahore Kingdom.

In consideration for this Maharaja Gulab Singh was to pay to the British Rs. 75 Lakhs in cash.

There was stipulation

in this Treaty about the British keeping a Resident or an army in Jammu

& Kashmir. The Maharaja however, recognized the Supremacy of the British

Government in token of which he was to present annually to the British

Government one horse, 12 hill goats and 3 pairs of Kashmiri Shawls.

The amount

to be paid was reduced to Rs. 75 lakhs from one crore because the British

decided to retain in their own hands the territory between the Beas and

the Ravi which includes the Kangra district of the Punjab because of the

strategic value of Nurpur and Kangra forts. The territories of which Gulab

Singh was thus recognized as an almost independent ruler also included

the area between the Jhelum and the Indus in which Rawalpindi and Islamabad,

the capital of Pakistan, are situated. Since this area was too far removed

from Jammu, he approached the British to exchange it for certain plain

area near Jammu. Thus the Jhelum instead of the Indus became the western

border of this kingdom.

Kashmir valley

was then controlled by Shaikh Imamuddin as Governor appointed by the Lahore

Darbar. He was secretly instructed by Lal Singh not to hand over the possession

of the valley to Gulab Singh. As a result he put up stiff resistance to

the vanguard of Gulab Singh's army when it reached Kashmir to occupy the

valley in terms of the Treaty of Amritsar. Wazir Lakhpat, one of his ablest

generals, lost his life in this campaign. It was only after the British

had put pressure on Lahore Darbar and a new army was despatched to Kashmir

that Gulab Singh could occupy the valley. Thus he obtained possession of

Kashmir valley through the Treaty of Amritsar, made effective by force

of arms.

After he occupied

Kashmir, Col. Nathu Shah who controlled Gilgit on behalf of the Lahore

Darbar transferred his allegiance to Gulab Singh who thus becarne master

of Gilgit as well. Thus by 1850, Gulab Singh had become both de facto and

de jure master of the whole of Jammu & Kashmir state including Jammu,

Kashmir valley, Laddakh, Baltistan and Gilgit. The States of Hunza, Nagar

and Ishkuman adjoining Sinkiang were added to the State by his son Ranbir

Singh some years later. Some time later the ruler of Chitral also accepted

suzerainty of Jammu & Kashmir. Chitral remained a feudotary of the

Dogra Kingdom until 1947.

It is clear

from the above account that Jammu & Kashmir State as at present constituted

is the creation of Gulab Singh who welded together such diverse and far-flung

areas as Jammu bordering on the Punjab, Laddakh bordering on Tibet and

Gilgit bordering on Sinkiang, Afghanistan and USSR across the Pamirs.

It is wrong

to describe the British grant of dejure recognition to him as master of

Jammu & Kashmir as a sale deed. He was already in possession of most

of this territory and would have fought for it if the British had tried

to dispossess him. Actually the British had earlier offered him this territory

even without payment of any money. He was forced to pay this money simply

because of his own loyalty to the Lahore Darbar and the chicanery of Lal

Singh.

Some writers

have been very critical of Gulab Singh for not taking part in first Anglo-Sikh

war of 1846 and for making a separate treaty with the British after the

Treaty of Lahore under which the Lahore Darbar ceded the territories that

were already in Gulab Singh's possession and Kashmir valley to the British

in lieu of the war indemnity which it was not in a position to pay. This

criticism is unjustified.

Gulab Singh

cannot be blamed for keeping away from Lahore after the brutal murders

of his brothers and nephew. He too might have met the same fate had he

been in Lahore when Khalsa army went on the rampage. However, he was opposed

to pitched battles with the British and had suggested attack on Delhi.

His advice was not heeded. In the circumstances he could not be faulted

for remaining aloof.

Jammu was his

ancestral home. Other territories including Laddakh and Baltistan had been

conquered by him with his own resources without any help from Lahore Darbar.

As Governor of Peshawar and Commandant of Sikh forces in the first Anglo-Afghan

war he had made his own assessment of the British. Developments in Lahore

after the death of Maharaja Ranjit Singh in 1839 had convinced him that

foreboding of Ranjit Singh that all territory will come under British away

- "sab lal ho jayega" was coming true. Being a realist he decided to salvage

as much of the Lahore kingdom as possible for himself. He was in a strong

position. The British were not in a position to take on his Dogra armies

at that time. They therefore, adopted a realistic course of accepting the

de-facto position and get the indemnity money they needed so badly in the

bargain. Gulab Singh got his de-facto position recognized by the wily British

not by their grace but by pressure of the realities on the ground. Had

he not been able to safeguard his possessions and get dejure recognition

for them, Jammu, Kashmir, Laddakh, and Gilgit would have gone the way of

Punjab and would have become ipso-facto parts of Pakistan in 1947.

It is, therefore,

necessary that an objective assessment of Gulab Singh's achievements be

made in the light of ground realities at that time. He was not only a great

soldier but also a statesman. It is true that he was primarily concerned

with his possessions and his interests. But what he achieved had far reaching

impact on the interests of Hindustan as a whole. His foresight and constructive

statesmanship, therefore, deserve praise and not condemnation.

It is unfortunate

that such writers have failed to give not only Gulab Singh what was his

due but have also failed to give due praise to his general, Wazir Zorawar

Singh, whose military campaigns in Laddakh and Tibet can be compared with

the campaigns of Hannibal and Napolean.

Zorawar Singh

was one of the greatest military captains of the world. His prowess, quality

of leadership and the strategy he adopted in his trans-Himalayan campaigns

must be studied by the military leaders of free India with pride.

The events

of circumstances leading to the creation of Jammu and Kashmir State as

detailed above naturally made it a heterogeneous conglomeration of diverse

and distinct areas devoid of any basic unity, geographical, social or cultural,

except obedience to a common crown. Geographically it presented a delightful

panorama of alluvial plains to the south of Jammu, obtained in return for

the territory lying between the Jhelum and the Indus, melting into hills,

hills melting into snowy mountains and mountains into high arid and wind

swept plateaus of Laddakh and Baltistan with the vale of Kashmir as an

emerald set in the centre inviting the wistful glances of all Asian neighbors.

A Conglomeration

of Six Distinct Regions

Broadly speaking

geography divides this State into the basin and catchment areas of three

major rivers - the Chenab, the Jhelum and the Indus. The entire area from

the Plains of Punjab to Panchal range of the Himalayas is drained by the Chenab. The valley of Kashmir and western districts of

Mazaffarabad, Poonch

and Mirpur form the basin of the Jhelum. The Indus drains the waters of Laddakh, Baltistan and Gilgit before turning south and cutting through

the Himalayas to reach the Punjab plains.

From the linguistic

and cultural point of view, this vast and varied state of 84471 sq. miles,

bigger than many of the modern European States, whose only unity lay in

a uniform and unified administrative system, could be divided into six

distinct regions with distinct identities. A clear understanding of the

historical and cultural background of these different peoples and regions

and a proper appreciation of their economic, social and cultural moorings

and political aspirations is essential for proper understanding and appraisal

of the Kashmir problem.

Jammu

The first and

the foremost part or region is "Dugar" better known as Jammu, the homeland

of the founder of the State, as also of the Dogra people. It is directly

contiguous to East Punjab and Himachal Pradesh in India and includes the

entire districts of Jammu, Kathua, Udhampur including Bhadarwah and Kishtwar

and the eastern parts of the erstwhile districts of Riasi and Mirpur of

the administrative province of Jammu. It stretches from the Ravi in the

east to roughly the cease- fire line in the west and from Suchetgarh in

the south to the Banihal pass in the Pir Panchal range in the north. Its

total area is about 12,000 sq. miles.

The inhabitants

of this region are Dogras. Thousands of Kashmiris have also settled in

the Ramban and Kishtwar areas. The Gujars, who speak a Pahari dialect,

inhabit the western part of Riasi District. The total population of this

region is about 30 Lakhs of which over 20 Lakh are Hindus. The spoken language

of this region is Dogra which includes a number of Pahari dialects and

is written in the Devnagari script.

The whole of

this region is mountainous except for a narrow belt bordering on the Punjab.

A few beautiful valleys like that of Bhadarwah, which is known as "miniature

Kashmir," lie in its interior. The Chenab flows right through this region

draining its waters and carrying its valuable timber wealth to Akhnur near

Jammu before it enters the Punjab state of Pakistan. The chief occupations

of its people are agriculture and soldiering. Thousands of hardy Dogras

from this region serve in the Indian army. Maize and rice are the main

agricultural crops. Lower Himalayan ranges traversing this region are covered

with rich fir and deodar forests. Lumbering, therefore, is an important

industry. Forest produce, lime, resin, honey, 'Rnardana' and medical herbs

besides timber form the chief exports of this area. It is also the richest

part of the state in respect of mineral wealth. Extensive deposits of coal,

mica, iron and aluminium are known to exist in it.

Bhadarwah,

which is now linked up with Chamba in the Himachal Pradesh and with Batote

on the Jammu- Srinagar highway by motorable roads, is perhaps the most

beautiful part of this region. Its fruits are superior even to those of

Kashmir Valley and the natural scenery is no less charming. Kishtwar, which

lies just to the north of Bhadarwah, is famous like Kashmir for its saffron

fields. It forms a direct link between Dugar and Laddakh which lies to

its north.

Politically,

this area had remained divided into a number of small principalities ruled

over by Hindu Rajas owing occasional and doubtful aIlegiance to the powerful

empires rising in the plains till their unification into one compact whole

by Raja Gulab Singh. Jammu is the chief town of this region and the winter

capital of the whole state.

Socially, culturally,

and economically the people of this region are indissolubly linked with

the Dogras of East Punjab. In fact, the Dogra belt spread over Gurdaspur,

and Hoshiarpur districts of East Punjab, Kangra, Chamba and Mandi districts

of Himachal Pradesh, and the Dugar zone of the Jammu and Kashmir State

forms a compact homeland of the Dogras. Naturally, therefore, the people

of this region aspire to remain connected with India, irrespective of what

happens to other parts of the State.

From the Indian

point of view this is the most important part of Jammu and Kashmir State.

It forms the only direct and feasible link between India and the rest of

the State. The Pathankot-Jammu road and the Jammu- Banihal road that connect

the rest of India with the Kashmir Valley pass entirely through this region.

The choice of its inhabitants on the question of accession is beyond doubt.

Its mineral and power resources are immense.

Laddakh

To the north-east

of Dugar lies the extensive plateau of Laddakh. It is directly contiguous

to Himachal Pradesh. It was being ruled over a local Buddhist Raja, Tradup

Namgyal, when it was conquered by Wazir Zorawar Singh between 1834 and

1840 for his master Maharaja Gulab Singh. He entered Laddakh through Kishtwar

in Dugar and not through Kashmir. Its total area is about 32,000 square

miles and total population is about two lakhs, majority of which are Buddhists.

This is a very

backward area. The inhabitants eke out a bare existence by rearing yaks

and cultivating 'Girm," a kind of barley, in the few high and dry valleys

of the Indus. Their chief pre-occupation is their religion. They give their

best in men and material to the numerous monasteries that act as an oasis

in a veritable desert. The wealth, art and learning of the people is Concentrated

in these monasteries. Some of them Contain rich collections of ancient

Buddhist literature in Sanskrit or its translations in Tibetan. The population

is kept down by social customs like polyandry and dedication of girls and

boys to the monasteries and is being further reduced by slow conversion

to Islam through inter-marriages with Balti and Kashmiri Muslims. The offspring

of these mixed marriages are known as "Arghuns." They form the trading

community.

Leh, the chief

town of this region, situated on the Indus at a height of more than 11,000

feet above sea level is one of the highest habitats in the world. It used

to be the seat of the Raja of Laddakh before the Dogra conquest. After

the conquest and formation of Laddakh district, it became the summer headquarters

of the District Officer appointed by the State Government. It is now connected

with Srinagar by a well-kept highway. It crosses the high mountains dividing

Laddakh from Kashmir through the Yojila pass. Leh used to be, till a few

decades back, a great mart for Central Asian trade. Caravans laden with

silks, rugs and tea used to pour into Leh frorn distant Tashkand, Kashghar

and Yarkand. These goods were exchanged here for sugar, cloth and other

general merchandise from India. But since the absorption of these Central

Asian states into empires of Russia and China, this trade has virtually

stopped. But the strategic importance of Leh as a connecting link with

Central Asia rernains.

A part of Ladakh

was over-run by the Pakistanis in 1947- 48, when, after capturing Askardu

and Kargil, they began their advance on Leh. Several hundred innocent Buddhists

were murdered and many monasteries were looted, despoiled and desecrated

by the invaders. But the epoch - making landings of the I.A.F. Dakotas

carrying the sinews of war on the improvised airfield of Leh at more than

11,000 feet above sea level and the brilliant winter offensive of the Indian

army leading to the capture of the Yojila Puss and Kargil saved Leh and

the rest of Laddakh from going the way of Gilgit and Baltistan.

Baltistan

The third distinct

region of the State is Baltistan inhabited by the Balti people. It lies

to the north of Kashmir and west of Laddakh. For administrative purposes,

it was grouped with Laddakh to form the district of that name. Its total

area is about 14,000 square miles and total population about 1,30,000 according

to the 1941 census. Almost all of them are Muslims by religion.

Baltistan was

conquered by Wazir Zorawar Singh along with Laddakh between 1834 und 1840.

Before that it was being ruled over by petty Muslim Rajas of Laddakhi descent.

The chief town of this region is Askardu which used to be the winter headquarters

of the Laddakh district. Situated on the Indus like Leh, it has a fort

of great natural strength.

Baltistan was

overrun by Pakistani troops and Gilgit Scouts during the winter of 1947-48.

The State garrison in the Askardu fort held on gallantly for some months.

But no effective help could be sent to them from Kashmir because the Yojila

pass had passed into the control of Pakistan and aid by air was made difficult

by the enemy occupation of all possible airstrips.

The winter

offensive of the Indian Army in 1948 succeeded in the recapture of the

Yogila Pass and the town of Kargil beyond it, which commands the road to

Leh and Askardu. Thus a part of Baltistan came back into Indian hands but

its major portion including the town of Askardu still lies on the Pakistan

side of the cease- fire line.

Balistan is

not of much economic or strategic importance. It is sandwiched between

Laddakh and Gilgit. But it has provided Pakistan with a convenient route

for advance toward Yojila Pass and Leh from its base in Gilgit. Its main

produce are barley and fruits especially apricots. Some of the valleys

of tributaries of the Indus in this zone are quite fertile. The people

of this part of the State are very backward and till the time of Pak invasion

of 1947, were quite indifferent to political developments in Kashmir and

Jammu. But now they have been infected by Pakistani propaganda. Pakistan

is known to have linked Askardu with Gilgit by a motorable road and has

also built a big air base there. It is now the base of supply for Pak troops

on the Siachin Glacier.

Gilgit

The fourth

distinct region of the State is Gilgit. It includes the Gilgit district

and feudatory states of Hunza, Nagar, Chillas, Punial, Ishkuman, Kuh and Ghizar. The total area of this region is about 16,000 square miles and

the total population in 1941 was about 1,16,000. Almost all of them are

shia Muslims. Most of them are followers of the Agha Khan. They belong

to the Dardic race and are closely connected with the Chitralis in race,

culture and language. Shina and Chitrali are the two languages spoken by

them.

This region

was conquered with great difficulty by Maharaja Gulab Singh and his son

Maharaja Ranbir Singh between 1846 and 1860. Thousands of Dogra soldiers

lost their lives in the campaign that led to the conquest of this inhospitable

but strategically very important region. It is here that the three Empires,

British, Chinese and Russian met. The independent Kingdom of Afghanistan

also touches its boundaries.

The strategic

importance of this region increased very much after the advent of air force

and the expansion of the USSR and Communist China towards the Central Asian

regions adjoining Gilgit and Baltistan. This region contains the fertile

valley of the Gilgit river, a tributary of the Indus. The name of the entire

region is derived from the name of this river.

Gilgit is divided

from Kashmir by the same Himalayan range which divides Kashmir from Laddakh

and Baltistan. But the direct and the shortest link between Gilgit and

Kashmir is provided by another Pass, the Burzila. It is more than 13,000

feet about sea level and, therefore, remains closed for many months in

the year. The access to Gilgit from Pakistan via Peshawar is comparatively

easy.

The whole of

Gilgit including the Burzila Pass now lies on the Pakistan side of the

cease fire line. The state garrison as also the military governor appointed

by the State were over-powered by Pakistani troops with the aid of the

local militia, the Gilgit Scouts, during the winter of 1947. Gilgit has

since been developed as a major military base by Pakistan.

From the economic

point of view Gilgit is not rich though it has vast potentialities. Its

climate is bracing and temperate. Temperate fruits like apple, apricot,

and almonds grow in abundance. "Zira", (or cumin), a valuable spice, however,

is the most valuable produce of this area and is exported in large quantities.

The people are healthy and fair-colored. Polo is their national game in

which they excel. They had come under Hindu and Buddhist cultural influence

quite early. Gilgit probably formed a part of the Khotan Province in Ashoka's

empire. A recent find of Buddhist and Sanskrit books near Gilgit confirms

this view. A class of people among them is held in high esteem. They are

expected not to eat beef and to remain clean. They were perhaps the Gilgiti

Brahmins before their conversion to Islam.

Till 1947,

these people were very much devoted to the Maharaja and his Government.

They protested against the lease of Gilgit to the British. But after the

partition, they, especially the Rajas of Munza and Nagar, were incited

by the Pakistanis and the British Political Agent to press the Maharaja

for accession to Pakistan. They later became collaborators of the Pakistanis

and revolted against the Maharaja's government.

Punjabi

Speaking Belt

The Punjabi

speaking districts of Mirpur, Poonch and Mazaffarabad lying along the river

Jhelum which forms the western boundary of the State, constitute the fifth

district region of the State. Mirpur formed a part of the Jammu province,

Muzaffarabad of Kashmir and Poonch was a big "Jagir" ruled over by a descendant

of Raja Dhian Singh, younger brother of Gulab Singh, who rose to be the

Prime Minister of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. The total area of this belt is

about 6,000 square miles and total population about 11 lakh. Nearly a lakh

of them were Hindus. They have been either killed or squeezed out by the

local Muslims with the help of Pakistani invaders. The chief towns of this

area are Mirpur, Poonch, which is still in Indian hands, and Muzaffarabad

on the confluence of the Jhelum and the Krishna Ganga. This last town is

now the headquarters of the so-called "Azad Kashmir" government. Mirpur

and Poonch were conquered by Gulab Singh for Maharaja Ranjit Singh from

the loca Muslim Rajas. Muzaffarabad was acquired by him after he had occupied

Kashmir by defeating its Muslim Sultan in a bloody battle.

Parts of this

region are quite fertile. But the real importance of this region lies in

its warlike manpower. Poonch area alone gave about sixty thousand recruits

to the Indian army during the Second World War. The Sudhans, the Jarals

and the Chibs who inhabit this area are Rajput converts to Islam. This

area has an additional importance for Pakistan because the river Jhelum

which carries the rich timber wealth of Kashmir and Karen forests flows

through it. The headworks of the Upper Jhelum Canal at Mangla are situated

near Mirpur in this zone. This region also links the West Punjab and the

North-Western Frontier Province with the valley of Kashmir.

The people

of this region are bound in bonds of common religion with those of Hazara,

Rawalpindi and Jhelum districts of West Punjab. They actively sided with

the Pakistani raiders when the latter invaded the State from that side.

At present most of this region, except the towns of Poonch and Mendhar,

lies on the Pakistan side of the cease-fire line which runs just three

miles from the town of Poonch.

Kashmir

Valley

In the centre

of the State, surrounded by the diverse regions and peoples mentioned above

and cut off from them by high Himalayan walls, lies the beautiful valley

of Kashmir, the 'Nandan Vana' of India.

These geographical,

and linguistic regions of the State provide the geo-political background

of the Kashmir problem. The attitude of the people inhabiting these distinct

regions toward the partition of India and the developments that have taken

place since then, have their roots in hundred years of Dogra rule over

this vast and heterogenous state. A peep into these hundred years is therefore

necessary for proper understanding of the genesis of Kashmir problem.

FOOTNOTE

2. Making of

Kashmir State by K. M. Panikkar: pg. 98.

|

No one has commented yet. Be the first!