Chapter 11

Shadow of Cold

WarThe

developments leading to the dismissal and arrest of Sh. Abdullah in August

1953 and the signing of USA - Pak Military Pact early in 1954 were closely

linked up with the cold war politics of the two power blocs. They in their

turn contributed to a further intensification of the cold war in regard

to Kashmir which made an objective approach and a negotiated settlement

of the problem inside or outside the U.N.O. all the more difficult.

Internally,

these developments were closely linked up with Sh. Abdullah's personal

ambition to secure absolute power for himself in the Kashmir valley. To

aehieve this end, he leaned first on the Communists who gave him the idea

of independent Kashmir but later moved toward the west, particularly the

USA to the great chagrin of the Communists.

The opportunity

to cultivate the friendship of the Western leaders and secure their sympathy

for his pet plan was provided to him by his successive visits to Europe

and the USA as a member of the Indian delegation to the United Nations.

The ruling circles in the USA had already veered round to the idea of a

partition of Jammu and Kashmir between India and Pakistan more or less

on the basis of 'status quo' with freedom for Kashmir valley to decide

about its own future through a plebiscite under U.N. auspices. This fitted

in well with Sh. Abdullah's own ambition. He therefore, felt encouraged

to give out his mind in an interview to Michael Davidson of Sunday Observer

and New Scotsman in May 1949. He was reported to have said, "Accession

to either side cannot bring peace. We want to live in friendship with both

Dominions. Perhaps a middle path between them with economic cooperation

with each will be the only way of doing it".

The Government

of India was taken aback by this statement of Sh. Abdullah. Sardar Patel,

who had by that time integrated over 500 princely States but had scrupulously

refrained from taking interest in the handling of Kashmir problem because

of Pt. Nehru's insistence upon treating it as his close preserve, for once

thought it necessary to put his foot down on Sh. Abdullah's amibition.

His one frown made Sh. Abdullah realise that he could not take support

of New Delhi for granted.

The incident

made Abdullah uneasy and fearful of Sardar Patel who as Home Minister was

getting authentic reports. About Sh. Abdullah's activities and policies

which showed that he had scant respect for India's wider national interests

and the aspirations of the people of Jammu and Ladakh regions. But commitment

of the Government of India about plebiscite had enboldened him so much

that he began to act as an arbiter. He retaliated by expelling Colonel

Hassan Walia, the chief of Indian Intellegence outfit in Kashmir. It was

a direct challenge to Sardar Patel who as Home Minister was in charge of

central intelligence agencies. He summoned Abdullah to Delhi for explanation. Sh. Abdullah took his patron Pt. Nehru along with him when he met the Sardar

at his residence.

According to Sh. Abdullah, Sardar Patel gave him a bit of his mind. He told Pt. Nehru

in his presence that India had lost the game, and should better pullout

of the valley. 1

Being a nationalist

and realist Sardar Patel had better grasp of the developing situation in

Jammu and Kashmir state particularly after the publication of Dixon proposals.

If he had his way he would have put Sh. Abdullah in his place, integrated

Jammu and Ladakh regions with India and allowed Abdullah and his Kashmiri

followers to fend for themselves in the valley. Plebiscite, if held, would

have exposed secularism of Sh. Abdullah and his flock. The valley then

might have gone the way of other Muslim majority regions of the State. Sh. Abdullah would have then cooled his heels in some jail of Pakistan.

The death of

Sardar Patel toward the end of 1950 removed from the Indian scene the one

man who could have kept Sh. Abdullah's ambition in check and cleared the

mess that Pt. Nebru had made in Kashmir by his unrealistic and erratic

handling of the problem from the very beginning. Sardar Patel, himself

told the present writer when the latter requested him to do something about

Kashmir, that he would set things right there in one month, but he was

not prepared to take the initiative unless Pt. Nebru specifically requested

him to do so. Whether it was gentleman's agreement between the two giants

of the Indian politics not to interfere with each other's sphere of activity

or deliberate self-denial on the part of Sardar Patel, it is difficult

to say. But the fact remains that while Sardar Patel, was able to integrate

500 and add princely states including Hyderabad with great efficiency and

success within two years. Pt. Nehru made a mess of Kashmir in spite of

the huge sacrifices in men and material and camplete and unstinted support

of the nation to him in the matter. With the passage of time even the worst

critics of Sardar Patel have begun to admit that left to him the Kashmir

issue would have been settled long ago in keeping with national honor and

national interests. That will remain in the eyes of history, which is no

respecter of personalities. The measure of Sardar Patel's greatness as

a statesman and administrator as compared to Pt. Nehru whose handling of

Kashmir issue will go down in history as an epitome of the failure of a

man who with the best of opportunities and favorable circumstances made

a mess of everything he handled.

Deterioration

in the internal situation of the State after that was as rapid as it was

disconcerting for India. Elections to the Constituent Assembly of the State

were held in 1951. But they were so conducted that most of the candidates

of the Praja Parishad, the only Opposition party in the State, were eliminated

at the nomination stage by rejecting their nomination papers. The rest

were forced to withdraw for want of assurance that elections would be fair

and free. As a result, all the 75 nominees of Sh. Abdullah's National Conference

got elected unopposed.

The Constituent

Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir was supposed to ratify the accession of the

State to India and adopt the Indian Constitution, in the rnaking of which Sh. Abdullah and three other representatives from the State had an equal

hand, for the State as well. But Sh. Abdullah gave it quite a different

idea of its powers and scope from the very beginning. He told it that it

was "one hundred percent sovereign" and that "no Parliament, be it that

of India or of any other country, has authorization here." Referring to

independence as a possible solution he observed on March 25, 1952, "suppose

for the sake of argument that the people do not ratify this accession the

position that will follow, would not be that as a matter of course Kashmir

becomes a part of Pakistan. No, that would not happen. That cannot happen

legally or constitutionally. What would happen in such eventuality would

be that the State would regain the status which it enjoyed im mediately

preceeding the accession. Let us be clear about it."

Simultaneously,

he began to speak in the same strain outside the Assembly. His main object

thus appeared to be to put pressure on the Government of India to make

definite commitment about same sort of independence for Kashmir before

the Constituent Assembly ratified accession. Thus he secured a free hand

to abolish the Dogra ruling dynasty and have a separate flag and Constitution

for the State. Accordingly the hereditary Dogra ruler as the head of the

State was replaced by an elected president called Sadar-i-Riyasat, the

red flag of the National Conference was adopted as the State flag and machinery

was set up for drafting a separate Constitution for the State while the

question of ratification of accession was kept pending.

These separatist

moves and utterances of Sh. Abdullah sent a wave of resentrnent in Jammu

and Ladakh as also in the rest of India. The Praja Parished launched a

movement for the integration of the State with the rest of India like other

acceding States with a ccmmon Constitution, a common President and a cc

m mon flag. The popular discontent against discriminatory economic and

administrative policies of Sh. Abdullah's Government with regard to Jammu

added strength to this movement which spread to every nook and corner of

Jammu region. Thousands of people courted arrest and about two score persons

were shot dead for hoisting the Indian tricolour on the State buildings

in Jammu and for raising the slogans-

"Ek Desh Men

Do Vidhan

Ek Desh Men

Do Nishan

Ek Desh Men

Do Pradhan

Nahin Chalenge-Nahin Chalenge."

(Two Constitutions,

two Presidents and two Flags in the same country will not be tolerated.)

The patriotic

sufferings of the people of Jammu found sympathetic response from nationalist

India spearheaded by the late Dr. Shyama Prasad Mookerji who, ever since

his resignation from the Nehru Cabinet in April 1950, had been unofficially

acclaimed as Leader of the Opposition even though his own party, the Bharatiya

Jana Sangh, could return only three members to the first Parliament of

free India elected in 1952. He took up the cudgels on behalf of the Praja

Parishad inside and outside the Indian Parliament. Having failed to persuade

Pt. Nehru to sit round a table with the representatives of the people of

Jammu and Laddakh and meet their gnuine and patriotic objections to the

separatist policies of sh. Abdullah, he decided to extend the Satyagraha

started by the Praja Parishad in Jarnmu to the rest of India.

Sh. Abdullah,

who had the full backing of Pt. Nehru, instead of relenting became more

obdurate and aggressive. He intensified repression and many people were

killed for hoisting the national flag. As the reports of this repression

travelled out of the State, Shyama Prasad Mookerji decided to visit Jammu

and see things for himself. He asserted that as a citizen of free India

and a Member of the Parliament he was free to go anywhere in the country

without any kind of permit and, therefore, proceeded toward Jammu without

an entry permit in May 1953. It was expected that he would be arrested

by the Government of India for this defiance. But instead he was allowed

to cross the Ravi bridge at Madhopar and enter the State to be arrested

by the State authorities. This was arranged deliberately to keep him out

of the jurisdiction of the Indian Supreme Court which would have surely

released him on a reference being made to it.

Dr. Shyama

Prasad Mookerji along with Vaidya Guru Dutt, a leading physician and well

known writer, who accompanied him as his personal physician were taken

to Srinagar and detained there. After about a month, on June 23, 1953,

Dr. Mookerji died there in mysterious circumstances. Unofficial probe pointed

to medical murder. It sent a wave of resentment all over India.

In the meantime

within the National Conference as also in Sh. Abdullah's Cabinet a rift

was developing. The pro-Communist elements which had been the staunchest

protagonists of the independence for Kashmir had been alarmed by Sh. Abdullah's

tilt toward Anglo-American camp which had become very marked after his

last visit to Paris toward the end of 1951. Sh. Abdullah, it appeared,

had realized that his dream of an independent Kashmir was more likely to

come true with the help of the Anglo-American bloc which dominated the U.N.O. and the Security Council than the Communist bloc. He had therefore,

begun to shift his allegiance from his Communist friends inside and outside

Kashmir to the Western countries. As the Praja Parishad movement for fuller

integration of the State with the rest of India gathered momentum, he began

to rouse the communal sentiments in Kashmir in the name of Kashmiri nationalism

and demonstrate his indifference and disdain for the susceptibilities of

the people of Jammu and the Government of India in different ways. The

trend became particularly evident after the visit of Mr. Adlai Stevenson

to Srinagar early in May 1953. This alarmed the pro-Communist Ministers

of his cabinet. They now turned against him. Bakshi Ghulam Mohammed, the

right-hand man of Sh. Abdullah, joined hands with them. These internal

developments coupled with the pressure from outside resulting from Dr.

Mookerji's martyrdom made Sh. Abdullah desperate. But before he could show

his hand by dismissing the dissident Ministers and making a formal declaration

of his plan about independent Kashmir, Yuvraj Karan Singh, the only son

of Maharaja Hari Singh, uho had been made 'Sadar-i-Riyasat' - head of State

- after the abolition of the hereditary rule of the Dogra dynasty dismissed Sh. Abdullah and commissioned Bakshi Ghulam Mohammed to form a new Cabinet.

Sh. Abdullah was soon after arrested under Defence of Kashmir Rules.

This sudden

turn of events took by surprise both Pakistan and the USA which had begun

to lay great hopes on Sh. Abdullah for a solution of the Kashmir problem

suiting their ends. Their chagrin was clear from the hostile comments in

their press.

The Communists,

inside India and outside, on the other hand, hailed the overthrow of Sh.

Abdullah as a victory for themselves and started denouncing the USA in

the strongest terms. They thus successfully exploited the popular feeling

roused by the Jan Sangh and Sh. Abdullah's separatist policies for creating

an anti-A.nerican hysteria in India.

The pro-Communist

bias of India's neutralist foreign policy and the persistent support given

by the USSR and other Communist countries to India's stand on Kashmir in

the Security Council coupled with the failure of Indian external publicity

to properly educate the American public opinion about the justice of India's

case contributed to Pakistan's success in creating a powerful anti-India

lobby in the U.S. press and Congress. Many Americans genuinely began to

feel that India was moving toward the Communist bloc and that Pakistan

could be an asset, particularly because of the strategic situation of Gilgit

for containing the spread of Communism in Asia if it could be persuaded

to join the Baghdad Pact which was later re-Christened as Central Treaty

Organization (CENTO).

At the same

time there was a visible pro-American shift in Pakistan's foreign poliey

particu1arly after the assassination of its Prime Minister, Mr. Liaqat

Ali Khan in 1952. Even otherwise, the very genesis of Pakistan demanded

that her foreign policy should rlm counter to that of India. Having been

born out of hatred for the Hindus and Hindusthan, Pakistan's very existence

required that India was presented to her people as their chief enemy and

everything was done to strengthen Pakistan vis-a-vis India.

By the end

of 1953, it became evident that negotiations for a military pact between

Pakistan and the USA were moving toward a successful conclusion. The signing

of the pact was formally announced early in 1954.

India reacted

very strongly to this pact which meant substantial augmentation of military

strength of Pakistan with free supplies of armaments from the USA Pt. Nehru

referred to this situation in his letter of March 5, 1954, to Mr. Mohammed

Ali, the Pakistan Premier. He wrote "the U.S. decision to give this aid

has changed the whole context of Kashmir issue and the long talks we have

had about this matter have little relation to the new facts which flow

from this aid...." It changed the whole approach to the Kashmir problem.

It takes it out from the region of peaceful approach for a friendly settlement

by bringing in the pressure of arms."

Pakistan on

its part strongly resented the declarations of Bakshi Ghulam Mohammed after

his assumption of power that accession of Jammu and Kashmir State to India

was full, final and irrevocable. The actual ratification of accession by

the Kashmir Constituent Assembly soon after further irritated her.

A s a result,

the area of disagreement about the Quantum of forces to be retained by

either side which appeared to have been considerably narrowed by the direct

talks of the two premiers became wider than ever before. Pt. Nehru insisted

that in the new situation created by the abundant supply of military aid

to Pakistan from the USA, "what we said at a previous stage about the quantum

of force had little relevance. We can take no risks now as we were prepared

to take previously and we must retain full liberty to keep such forces

and military equipment in the Kashmir State as we may consider necessary

in view of this new threat to us."

Direct negotiations

having thus foundered on the rock of U. S. Pak Military Pact, Pakistan

Premier, Mr. Mohammed Ali, informed Pt. Nehru in his letter of September

21, 1954, that "in the cireumstances I am bound to conclude that there

is no scope left for further direct negotiations between you and me for

the settlement of this dispute. This case, therefore, must revert to the

Security Council."

Pakistan, however,

took two and a half years after the failure of direct negotiations to request

the Security Council to take up the Kashmir issue once again. The request

was made by Malik Feroz Khan Noon, the Pakistan Foreign Minister cn January

2, 1957, and the Security Council resumed debate on Kashmir an after interval

of nearly five years on the 16th of the same month.

Meanwhile,

the situation inside the State as also the attitude and approach of both

the countries to the proble m had undergone a lot of change. Within the

State, the most significant development was the unanimous decision of the

Constituent Assembly to ratify the accession and the specific declaration

in the Constitution adopted by it on November 17, 1956, that "the State

of Jammu and Kashmir is and shall be an integral pnrt of the Union of India."

This strengthened the hands of the Government of India which could assert

with justification that the people of the State had given their democratic

verdict in favor of accession to India.

While the unanimous

decision of the Constituent Assembly strengthened the Indian position,

the re- organization of "Plebiscite Front and Political Conference" by

pro-Abdullah elements in Kashmir valley and their open demand for a plebiscite

and accession to Pakistan strengthened the hands of Pakistan politically.

Militarily, her position had vastly improved because of the massive flow

of the latest armaments of all types together with military experts from

the USA. As a result, the attitude of the rulers of Pakistan became more

aggressive. Apart from carrying on a diplomatic offensive against India

all over the world, they began to actively organize and encourage acts

of sabotage through their agents within the State.

As a reaction,

India began to lean more and more upon the USSR and her satellites which

gave a further pro- Communist tilt to her foreign policy. The visit to

India of Marshal Bulganin, the USSR Premier, and Mr. Khruschev, the First

Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, toward the end of

1955 and their open declaration at Srinagar of December 10, 1955 "that

the question of Kashmir as one of the States of the Republic of India had

already been decided by the people of Kashmir" made the alignment of the

USSR with India on the question of Kashmir as explicit as that of the USA

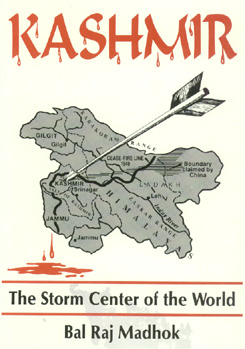

with Pakistan. The cold war had now entered Kashmir itself. It began to

be looked upon as one of the storm centers of the world like West Berlin

where the interests of the two giants clashed directly.

The situatian

forced Pt. Nehru to do some re-thinking about the stand he hac taken regarding

Kashmir. Doubts as said earlier, had already begun to assail him about

the wisdom of the offer about plebiscite which was bound to be influenced

by religious considerations whenever and however it was held. The behavior

of Sh. Abdullah also shook him. The tone of his utterances about Kashmir

therefore changed. He began to voice his opposition to plebiscite openly

and the Indian Home Minister, late Pt. Pant, declared that Kashmir was

an integral and irrevocable part of India.

This change

of attitude was reflected in the stand taken by the Chief Indian delegate,

Krishna Menon, when the Security Council resumed debate on Kashmir. India

for the first tirne explicitly charged Pakistan of direct aggression and

declared that she had no obligatiaon to discharge till the aggression was

vacated. Indra's voluntary offer to consult the people, he said had been

redeemed through elections to the constituent Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir

whose actions were "declaratory and not creative." The legal right of India

over the whole of Jammu and Kashmir State, he asserted, flowed from the

lawful accession of the State by Maharaja Hari Singh which was full, final

and irrevocable.

Some hope of

a negotiated settlement outside the UN rose once again after the Military

coup in Pakistan which brought Marshal Ayub Khan to the helm of affairs

in Pakistan in 1959. As a soldier he had a greater consciousness of the

indivisibility of the Indo-Pak defense against possible aggression from

Communist China to meet which Indo-Pak amity was essential. He needed it

to stabilize his own position as well. Furthermore, he was in a position

in the early days of his new found power to take a decision even against

the popular sentiments of the Pakistani people. He was even more keen for

the settlement of the Canal Waters dispute in which India had a whip hand

over Pakistan. Had Indian diplomacy shown any grasp of realities, it would

have insisted upon a package deal embracing all Indo-Pak disputes such

as the Canal Waters, Kashmir, evacuee property, paratition debt and treatment

of the Hindu minority in East Pakistan. But Pt. Nehru bungled once again.

A Ganal Water Treaty was signed at Karachi in 1960 which gave Pakistan

much more favorable terms than suggested by the World Bank Award.

With that ended,

the short lived Indo-Pak dentente brought about more by personal relations

between Mr. Rajeshwar Dayal, the Indian High Commissioner at Karachi, and

Marshall Ayub who happened to know each other well since pre-partition

days than by a real change of heart on both sides. The old game of mutual

accusation began once again. Communist Russia saw in the military regime

of Marshal Ayub a greater threat to her position in Ausia and, therefore,

became more vociferous in her support to India over Kashmir. She began

to use her veto to prevent any resolution to which India was opposed, being

passed by the Security Council.

This reduced

the discussions in the Security Council to just debating bouts between

itriolic Krishna Menon of India and suave and swifty Zaffarullah Khan of

Pakistan who began to exploit that world forum to malign India by repeating

baseless charges against her which were given wide publicity all over the

world.

As a result,

world opinion began to be influenced in favor of pakistan. There could

be no greater condemnation of the Indian Foreign policy and its exponents

that the people all over the world have a greater understanding and appreciation

of Pakistan's point of view about Kashmir than that of India in spite of

the truth and justice of the Indian case.

While these

pointless exercises in histrionics were going on in New York, Communist

China had starated fishing in the troubled waters of Kashmir cutting across

the cold war politics of both USA and the USSR.

The entry of

Communist China on the Kashmir stage as a third claimant to large chunks

of its territories introduced a new factor in the Kashmir situation; it

gave a new turn to the Kashmir problem.

FOOTNOTE

1. Atish-i-Chinar,

Page 513.

|

No one has commented yet. Be the first!