Mekhal Ritual of Kashmiri Pandits

By Dr. S.S. Toshkhani

“Mekhal”

is what the Kashmiri Pandits call upanayana or yajnopavit (sacred thread

investiture) and the whole range of ceremonies connected with it, though wearing

the mekhala or the girdle of Munja grass is only one of them. How they came to

use the word for the whole samskara is not clear. But it seems that at some

point in time it must have been for them the most important part of the sacred

thread investiture ceremony as it stressed the vows of celibacy and purity of

conduct as an essential prerequisite for the initiate to go to the Acharya to

learn. Actually, upanayana, with which it has become synonymous, was in the

beginning an educational samskara which was performed when the teacher accepted

to take charge of the student and impart necessary education to him. According

to Dr. Rajbali Pandey, it was made compulsory to make education universal.

Slowly it began to loose its pure educational sense and assumed a ceremonious

character with the investiture of the sacred thread, which took place at the end

of the yajna performed to mark the initiation and became the main ritual. In

course of time the boy initiated with the Gayatri mantra to enable him to read

the Vedas, was regarded as having acquired the status of a dvija or

‘twice-born’.

Whatever the case may be,

in Kashmir the samskara, whether called “mekhal” or yajnopavit, became a package

of about twenty-four samskaras from vidyarambha or learning of alphabets to

samavartana or the end of studentship. Interestingly, these include elements

from even the prenatal samskaras like garbh-adana and siman-tonnayana. Even

kahanethur (namakarana) and zarakasay (chudakarana or the first tonsure) if not

performed at the prescribed time can be combined with it. This has made mekhal

or yajnopavit a prolonged affair lasting for hours together. However, it is the

wearing of the sacred thread to which the greater significance or sanctity is

attached. That may be so because it has come to be regarded by the Kashmiri Brahmans,

as by Brahmans elsewhere in the country, an essential symbol of their Hindu

identity.

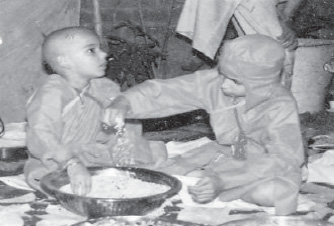

Mekhal Maharaza in a

Mekhal ceremony.

Let us have a look at some

of the peculiarities of the samskara as performed by the Hindus of Kashmir.

According to Laugakshi, the upanayana ceremony of a Brahman boy should be

performed in the seventh year from birth or in the eighth year from conception,

that of Kshatriya in the ninth year and that of a Vaishya in the eleventh year:

“saptame varshe brahmanasyopanayanam navame rajanasya ekadashe vaishasya”. This

differentiation between the ages of the initiates, however, has no relevance for

the Kashmiri Hindus today as there was hardly any Kshatriya or Vaishya left

among them after the advent of Islam in Kashmir. Optional ages have also been prescribed in the Grihyasutras in case of exigencies, the time limit for a

Brahman boy being sixteen years. As the samskara has become purely ceremonial

today, even this extended time limit is hardly adhered to and it is performed at

a convenient time, generally a few days before marriage.

A uniquely Kashmiri and an

essential preliminary ceremony performed a day or two prior to upanayana (and

also marriage) is Divagon. The etymology of the word ‘divagon’ is not clear but

it is probably derived from the Sanskrit ‘devagamanai, meaning ‘arrival of the

gods’. The ceremony is performed for invoking the presence of gods, especially

Ganesha and the Sapta Matrikas or seven mother goddesses, to bless the initiate

or the boy or girl to be married. It begins with a ritual bath, called

kani-shran, which is given to the initiate by five unmarried girls, pancha kanya,

four holding a thin muslin cloth over his head at its four ends and the fifth

pouring consecrated water with a pitcher. These days usually the officiating

priest himself pours the water.

A havan is performed on

the occasion amidst chanting of mantras by the presiding priest with the

initiate offering oblations while facing the east. On the eastern wall, the

motif of the kalpavriksha, supposed to be the abode of the goddesses in

Nandanavana or the Garden of Paradise is painted with lime and vermilion. The

kalpavriksha or the ‘wish fulfilling tree’ has a shatchakra (hexagon) made at

its base symbolizing Shakti, and the drawing is called divta moon or the ‘column

of the gods’. At about the same time khir is prepared and poured into seven

earthen plates called divta tabuchi or ‘the plates of the gods’. Roth of rice

flour and monga varya or fried cakes of ground moong are placed over the khir.

The plates are consecrated with mantras and offered to the seven matrikas after

which the khir with the moong cakes are distributed as naivedya. At the end of

the ceremony, ladies take the seven earthen plates in a procession to river for

visarjana. They go singing hymns and folksongs in the praise of the goddesses

and praying for the long life and happiness for the initiate.

Another typically local

feature that literally adds colour to the ceremony is krul - a vine scroll

painted on the outer door of the house. This is usually done by the paternal

aunt of the boy who executes the design of flower-laden creeper in different

colours on a white background. As the design is being executed with the sacred

symbol Om at the top, ladies assemble outside and sing auspicious songs. A dish

called veris distributed with rice flour rot is among all present.

Though painting the krul-

krul kharun as it is called in Kashmiri- is sort of ritual art denoting

auspiciousness, it has all the elements of folk art. In fact, it is one of the

few Kashmiri folk arts still alive.

The divagon over, the

yajna for Upanayana is performed much in the same manner as Hindus elsewhere

perform it. A jyotistambha or jwala linga with a shatchakra base is drawn at the

head of the agnikunda, with a rectangular configuration showing ayudhas like the

mace, trident, bow and arrow etc. topped by a pataka. To the west of it seating

arrangement is made for the officiating priests, the chief of whom is called

‘tsandra taruk’, literally meaning ‘the moon among the stars’. The tsandra taruk

sits on a special seat and leads the reciting of the mantras and also monitors

the proceedings of the yajna. The child to be invested with the sacred thread is

taken under the canopy where his father lights up the sacred fire. Then his hair

is shaved off by the barber - in the ordinary way if he has already performed

his zarakasay.

Then he is given a bath

and made to wear a snana-patta (loincloth) kept in its place by a cotton cord

called atya pan which is tied round his waist. He is also given an upper and

lower garment dyed in saffron or yellow colour so that he is dressed up like a

Brahmachari. The Grihyasutras though prescribe that the clothes of a Brahman

initiate should be of kashaya or reddish colour. The ceremony of offering

clothes to the Brahmachari is described in detail in the Laugakshi Grihyasutra

along with the Vedic mantras to be recited on the occasion.

Kalasha Puja is performed

before the actual ceremony of Upanayana starts. The kalasha, a pitcher filled

with water, vishtara (shoots of kusha grass ) and walnuts, is an important

ritual object full of symbolic significance. It is consecrated by making

shrichakra and swastika marks on it with vermilion (sindoar) and placed on an

ashtadala kamala (eight-petaled lotus) drawn with lime or rice flour on the

ground at the ritual site towards the east and on the left side of the agnikunda.

Kalasha Puja is a prolonged affair as the kalasha is said to contain the entire

heavenly vault and is the seat of all the gods with Vishnu occupying its mouth,

Rudra its neck, and Brahma its bottom. The group of matrikas is known to reside

in the middle part. Indra, Kubera, Varuna and Yama all reside in it. Within the

kalasha the planets and the gods are bonded together and above it there are

seven naga deities guarding it. The kalasha is worshipped with flowers and rice

grains (arghya) and the presence of all these deities is invoked with

appropriate mantras so that the day is auspicious for the yajnopavit ceremony

that is about to be performed. Kalasha Puja begins with the hymn ‘ Omkaro yasya

moolam, portraying the Vedas as a wish-fulfilling tree (kalpavriksha) and

praying to it for protection. In fact the Puja is performed at the beginning of

all major rites of Kashmiri Hindus.

Mekhala-bandhana or

maunji-bandhana is in itself a most important ritual related to upanayana

performed in the process when a girdle of the Munja grass is tied round the

waist of the Brahmachari (called “mekhali maharaza” in Kashmiri). Laugakshi and

his commentator Vedapala elaborately describe this rite. Some symbolic acts take

place before the guru (the officiating priest) takes charge of the initiate to

be. The teacher makes the Brahmachari to go round the sacred fire and to place

his foot on a stone, asking him to be firm and steadfast. Then he touches the

heart of the pupil uttering the words: “Into my will take thy heart; my mind

shall thy mind follow; in my word thou shalt rejoice with all thy heart; may

Brihaspati join thee to me” (“mama vrate hridayam te dadami mama vachenekavrato

jushasva Brihaspatih tva mayanuktak mahyam”). After this the Brahmachari takes

curds thrice and approaches the teacher to be initiated. At this the teacher

ties the girdle round the waist of the boy with the words: “Here has come to me,

keeping away evil words, purifying mankind as a purifier, clothing herself by

power of inhalation and exhalation, with strength this sisterly goddess, the

blessed girdle: “pranapanabhyam balamabhajanti sakha devi subhaga mekhaleyam”.

The mekhala or girdle in

the case of a Brahman is to be made of Munja grass and at the end of upanayana

is to be replaced by a cotton girdle, but as this grass does not grow in

Kashmir, a girdle of Kusha grass or of cotton is tied. And strange though it may

seem, the rite is increasingly being discarded even though the yajnopavit

ceremony continues to be called mekhal.

The decks are now clear

for the main and the most important rite - the investiture of the sacred thread.

In Kashmir, wearing of the sacred thread was essential not only for initiating a

young boy into Brahmanhood by teaching him to recite the Gayatri mantra but also

an essential prerequisite that made him eligible for marriage. Yajnopavit, it

must be noted, continues to be retained as one of the most important rituals

because of this reason also. The astrologically chosen auspicious moment is,

however, generally strictly adhered to. The boy takes a few steps to the north

and it is his father who first puts the three cords of the sacred thread round

his neck, which is then replaced by the set of three cords which the priest

makes him wear with the mantra “yajnopavit am paramam pavitram”. In the

meanwhile the boy is made to look at the sun. He is to put on another set of

three-folds on being married -one for himself and one for his wife. While the

father of the boy has a definite religious role to play, the mother and other

close relatives gather around him with the ladies singing auspicious songs to

make it a colorful occasion socially and everyone rejoicing and having a sense

of participation.

There are some features,

peculiarly regional in character, which are introduced at this stage. In one of

them, to which we have referred earier, the ladies of the family enact a

performance closely resembling simantonnayana. With the help of mulberry twigs

(instead of Udumbara) husbands of these ladies put through the locks of their

hair strands of narivan or protection cord in a manner that they dangle

alongside the strings of their dejihors. It is believed that this helps newly

married women to become mothers soon.

Another peculiar feature

is the tekytal - the figure of the shrichakra over a rectangular configuration

painted with vermilion or saffron paste on the top of the ladies’ headgear. As

an option the design may be cut out on coloured or golden paper and pasted on

the headgear. Tekytal shows show deeply Shaktism or the Mother Goddess cult has

influenced the social and religious life of Kashmiri Pandits.

Yet another interesting

and typically local feature in the Yajnopavit ceremony of the Pandits is varidan.

Varidan is a kind of hearth specially made for the occasion by the potter,

having thirty-six holes on which thirty-six sanivaris or small earthen vessels

are placed for cooking rice for rituals purposes. The thirty-six holes

correspond to the thirty-sx categories mentioned in the Shaiva texts as the

basic constituents of the manifested world. As the sanivaris are very small and

are filled only ceremonially, rice is cooked separately also in a large pot to

serve the ritual purpose.

Having worn the sacred

thread, the Acharya gives him specific instructions about how to wear the

sacrificial cord on different occasions. He then gives him a deerskin to wear,

Laugakshi prescribes: “anah-anas-yam vasanam charishnu paridam vajyajinam

dadh-eyamiti vachayannaineyam charma brahmanya prachh-ativaigyaghram rajanyam

rauravam vaishya”. That is, the skin of a black deer should be given to a

Brahmana for wearing as an upper garment, the Kshatriya the skin of a tiger and

the Vaishya that of a Ruru deer. Today the skin of a spotted deer is obtained

for a Brahman boy for ceremonial wearing, the other two castes virtually not

exsiting among Kashmiri Hindus. Dr. Rajbali Pandey quotes the Gopatha Brahmana

as saying that “the deerskin was symbolical of holy lustre and spiritual

pre-eminence.” It inspired a Vedic student to attain the spiritual and

intellectual position of a Rishi”. At the time of receiving the deerskin, the

Brahmachari is made to look at the sun with the mantra tachchakshur devahitam”.

The Acharya (priest) now

hands over a staff to the Brahamachari so that he may set upon his journey as a

traveler on the path of knowledge. Laugakshi prescribes that the staff should be

of Palasha wood for a Brahman: “palasham dandam brahmanaya p-rayachchhati”. As

Palasha wood is not available in Kashmir, the Brahmachari is given a staff of

the mulberry wood, which is readily available. But today what the priest hands

over is a staff in name only; actually it is a twig which has no utility, except

ceremonial, the modern student no longer going to the forest to study.

Having equipped the

initiated with a girdle, deerskin and staff (which were considered necessary for

the Vedic student going to study at his Acharya’s place), the Acharya now

imposes five commandments on him: “A Brahmachari art thou.

Take water. Do the

service. Do not sleep in the daytime. Control your speech”. Vedpala, the

commentator of Laugakshi Sutras explains service (karma) as serving the Acharya,

studying the Vedas etc.

Repeating five verses

from the Vedas in which the Seven Rishis and the gods are requested to stimulate

his (the brahmacahri’s) intelligence, he is made to repeat a sixth verse also

which is a yaju about milking the sweet milk of the Vedas.

At this point the

Brahamchari is to be shown the reflection of Agni or the burning sacrificial

fire in a pot of ajya or clarified butter. This is called ajya darshan, which

has been distorted to ‘adi darshun’ in Kashmiri. According to Laugakshi’s

prescription, it is to precede bhiksha or the round for alms. Siting in front of

the sacrificial fire with his face towards the east, the Acharya is to teach the

most sacred Savitri mantra in the Gayatri metre (and therefore known as the

Gayatri mantra) to the Brahmana pupil, reciting it three times-”first pada by

pada then hemistich by hemistich” and last of all the whole verse so that he is

able to learn it properly.

Vedarambha, or the

beginning of the study of the Vedas and vidyarambha, or learning of the

alphabets, are both mixed up in the present way of performing the sacred thread

ceremony. What happens is that after offering him the panchagavya or the five

products of a cow (cow dung, cow’s urine, milk, curds and ghee), the teacher

(impersonated by the officiating priest) makes the Brahmachari write some words

on a thali in which finely powered mud is scattered. The words generally written

on this occasion are “Om svasti siddham” or “Om namah siddhaya” (Salutation to

the Siddhas). The script in which this was originally written came to be known

as the Siddham or Siddhamatrika script, an earlier form of Sharada. The teacher

would make the child read what was written and explain its meaning to him. It

may be noted that in Kashmir vidyarambha was regarded as a part of upanayana and

not a separate samskara. The rite has, however, almost gone out of vogue now.

It is now that the

Brahmachari gets up to ask for alms (bhiksha) for the Guru, which in effect

means to collect money for the officiating priest. The first person he is

supposed to approach according to the Kashmiri custom is his maternal aunt.

Observing the necessary decorum has to address a lady he approaches for alms

with bhavati bhiksham dehi, abid habi” (“Venerable lady, give me alms”) and a

man with “bho bhiksham dehi, abid hasa” (“Venerable Sir, give me alms”). The

etymology of the Kashmiri word ‘abid’ is, however, not clear. Some say it is the

Kashmiri form of the Sanskrit word ‘abheda’, but though phonetically plausible,

this does not sound convincing.

To conclude the yajna, the

priest summons everyone for the last ahuti, offering a handful of a mixture of

soaked wheat grains and flowers. This is called athiphol, literally meaning a

handful of grains and is to be offered as oblation. Everyone makes a beeline to

receive the athiphol, making it sure that he or she is present during the

samapti or the concluding moments of the day-long yajna. Hymns for the

pacification of the gods and the planets are recited in a chorus led by the

priests and there is a clamour for offering the athiphol into the fire as soon

as the priest pronounces the last “svaha”. The priest then sprinkles water from

the kalasha on everybody present and distributes the walnuts as naivedya. The

water thus sprinkled is called ‘kalasha lav’ and the walnut as ‘kalasha doon”.

What is most interesting

is that samavartana or the sacrament marking the end of the “student career” of

the boy and his “return” home from the house of the Guru is treated as a part of

the Yajnopavit ceremony. It is assumed that the boy invested with the sacred

thread has completed his “studies” and has come back to the family. This is

regarded as a very important period in the boy’s life as he is now supposed to

be ready to share the responsibilities of the world and get married. In

accordance with the spirit of Laugakshi’s ordain-ments, the boy Invested with

the sacred thread is given new clothes and shoes to wear instead of the

brahamachari’s garments. A muslin turban is tied round his head. He is made to

stand on the vyug or a colourful mandala. Someone, usually a young friend of the

initiate, or mekhali maharaza as he is called in Kashmiri, holds a parasol of

flowers over his head. He is then taken in a procession to the riverbank for

snana, the ceremonial bath as a snataka (one who has completed his studies).

There, the priest, who also accompanies him, gives him instructions about

washing the sacred thread and performing daily rites like the sandhya etc.. He

is also taught how to offer libations of water to gods and ancestors. After this

he returns home in a procession. In the meanwhile, ladies sing auspicious songs

and perform a special dance in a circle, the origin of which could go back to

centuries. This is a unique feature of the celebrations.

The yajnopavita

ceremonies do not end with the samavartana. On the next day a small homa known

as ‘koshal hom’ (Skt. ‘kushala homa’) is performed to thank the gods that all

has ended well.

Source: Kashmir

Sentinel

|